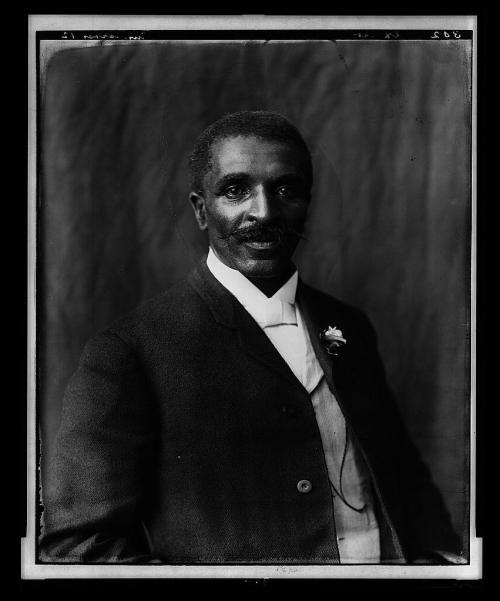

Image of George Washington Carver from Library of Congress

In Part III, we learned of George Washington Carver’s work at Tuskegee Institute and a few of his many inventions. This is the conclusion of George Washington Carver: Grandfather of Sustainability.

This brilliant mini-biography by Cheri Colburn first appeared in Greenwoman #2. It’s available in that issue, or in its entirety as an ebook on Amazon.com.

–Sandra Knauf

Seeds of Knowledge

Carver’s mission was clear, and he had no split loyalties: He desired to improve the lives of African Americans. This, of course, was the mission of Tuskegee itself, and Booker T. Washington sought to make it the mission of Tuskegee graduates as well. During commencement exercises, Washington would say things like “Go back to the place where you came from and work. Don’t waste too much time looking for a paying job. If you can’t get pay, ask for the privilege of working for nothing.” In that spirit, many little Tuskegees cropped up in small settlements and crossroads across the south from Virginia to Texas.

But this method of spreading ideas and information was slow for Carver’s purpose. He knew that black farmers were in crisis, and he wanted to ease their suffering sooner not later. So Carver created other ways to reach the farmers. His first year at Tuskegee, he set up an Experiment Station to show what could be done to enrich the soil and improve yields. One of his first experiments was to plow the old kitchen dump and plant several crops—onions, watermelons, and corn, to name a few.

This experimental garden became a showplace of productive fertility. The yield was high and the fruit and vegetables were large. So that his results would reach the people who needed the information, he invited Southern farmers (black and white) to visit the school. These “Demonstration Days” began small but soon grew to include hundreds of people yearning to know more.

Eventually the Demonstration Days became the Farmer’s Institute. Once a month, farmers and their wives would come to Tuskegee to receive information and instruction regarding a vast array of topics. They learned about soils and new crops, of course, and they also learned about homemaking: cooking, quilt-making, home-maintenance, and gardening. Basically, they received information about living more productive, healthier—and even more beautiful—lives.

With regard to the importance of beauty, Carver had a lot to say, and his thinking was right in line with Booker T. Washington’s. Washington was keenly aware that his school would be judged in large part on its appearance, and he wisely put Carver in charge of beautifying the campus. His first winter at Tuskegee, Carver began to transform the grounds. He had the land terraced, and in the spring (in addition to crops), trees, grasses, and flowers were planted.

As Tuskegee became more widely known, Northerners came to tour the campus and the surrounding farms. Booker T. Washington appealed to Southern blacks to spruce-up their properties by painting and whitewashing their homes, recommending that if they could not afford to paint the whole house to at least paint the front. This effort built on itself, and each year the properties looked better than the year before.

This effort greatly pleased Carver who felt that when one’s property was improved, so was one’s self-worth. There was a notable absence of pride in the appearance of Southern black homes, largely because improving a property owned by a white landlord might increase one’s rent. But the sharp contrast between Southern black homes and homes Carver had seen and helped to operate in the north was troubling to Carver. He encouraged people to pay more attention to this issue—to paint their homes, to plant flowers for their simple beauty, to maintain their living space (inside and out) for their own comfort and pleasure. Carver also had a sense that beauty—especially the beauty of a well-tended garden—brought one closer to God.

As time passed and farmers’ successes accumulated, excitement grew. More and more people attended the Farmer’s Institute and joined in the demonstrations, bringing their products for show and discussion. From this new pride grew the Macon County Fair—and soon after many other county fairs. Produce was the focus of the first fair (in 1898), but the women soon got involved, adding quilts and canned goods and needlework and home-cured meat to the displays. In 1903, Professor Carver spoke at the fair, extolling the benefits of (what else?) sweet potatoes and cowpeas.

In fact, Carver—a naturally quiet and modest man—had been a public speaker since his days at Ames. Back then, he would lecture at mycological gatherings (and of course and always in the classroom). But from his earliest days at Tuskegee, he spoke at small gatherings of farmers. Carver had a wagon that he drove into the countryside to reach people who could not attend Demonstration Days or the Farmers’ Institute. In it, he carried information about increasing profits and improving health—along with preserves, seeds, and even slips of roses to share. During these outings, Carver would often stay in the very modest homes of the people he was seeking to help. People were proud to have such an important man staying in their homes, and Carver was such a warm and unassuming person that any intimidation they might have felt quickly dissipated. He was not only admired but widely loved.

Carver’s speaking efforts and skills eventually reached a broad and prestigious audience. Widely known as a champion of the lowly peanut, Carver was invited one year to speak at the Peanut Growers’ Association. He astounded the (white) men who were in attendance with all he had learned and all of the products he had developed. As a result of that presentation, he was invited to speak on behalf of the Peanut Growers Association in a presentation to Congress in 1921. Peanuts from China were threatening the ability of US growers to make money on their crops, and they wanted Congress to institute a tariff. Carver waited many hours for his turn to speak and was then told that he only had a few minutes. He opened his boxes, began to speak, and as always, captivated the attention of his audience. He was allowed to deliver his entire message, and in the end, the peanut growers got their tariff.

Carver was not only a gifted speaker; he was an accomplished writer as well. As a part of his effort to disseminate information, he started publishing bulletins as soon as his work at Tuskegee began. He published the findings from the experiment station on topics such as soil conservation, crop rotation, and composting. He published bulletins nearly every topic that he thought would improve the lives and profits of Southern farmers: his peanut, cowpea, and sweet potato recipes; ways to preserve food; raising chickens and animal husbandry. Carver also wrote a syndicated newspaper column—“Professor Carver’s Advice”—in which he answered readers’ questions.

Whenever possible, Carver tried to be proactive regarding insect infestations and livestock diseases. He wanted farmers to have the information about these problems in hand before the problems arrived. And so it was with the boll weevil. When he recognized that a plague of boll weevils was advancing on Alabama, he published a bulletin advising farmers to diversify their plantings. Many farmers listened to him, creating a surplus of peanuts and sweet potatoes and inspiring his work (mentioned previously) to create commercial markets for these crops.

As if all of Carver’s aforementioned accomplishments are not enough to make us all feel like a bunch of TV-watching slackers, I will tell you that this (not so) little article barely scratches the surface of Carver’s contributions. He tracked the weather for the bureau in Montgomery. He continued to study fungi throughout his life and to make contributions to the general library of information on the subject. He also contributed to efforts to catalog medicinal plants for the Smithsonian Institution and the Pan-American Medical Congress. As a child in Mariah Watkin’s household, he was taught to believe in the curative powers of plants (and therapeutic massage as well). In this effort, he did not merely consider plants that were well-accepted as medicinal plants; sensing that many plants had poorly understood potential, he also those considered plants known only as household remedies.

Carver found time to help not only with lofty efforts but also with earthier concerns. From the beginning, farmers could bring him soils for testing and receive advice about fertilizer. They could bring weeds for naming and receive advice about control techniques. They could bring him well-water for testing and receive not only information about its potability but also the advice to install a pump: when you lower a bucket into a well, you are introducing bacteria from your hands, from the cattle you’ve just been tending, from the chickens who scratch in the surrounding dirt. Essentially he would help any common man who would also help himself.

A Worldwide Audience

As Carver became more and more widely known, important people from around the world began to consult with him. The Colonial Secretary of the German Empire came to Tuskegee to observe Carver’s cotton hybrids. A man from Queensland Australia acquired some seed from Carver and passed them to the Australian government. Carver heard back years later that the crop was being grown successfully all over the country.

African heads of state also consulted with Carver about his pet crop—the peanut of course. The peanut is a hearty plant (which is proposed to have come to America in the hulls of slave ships). Originally from the tropics, it can withstand draught better than most plants, shriveling in the heat but coming back to life with just a hint of moisture. In addition, it seeds itself by becoming top-heavy and bending its seeds back toward the earth. Peanut “milk” put an end to a tragic practice that had formerly been carried out in African nations where cattle could not be kept. When mothers died in childbirth, their infants were often buried with them. With the peanut, these children could survive.

In the mid-1930’s, Carver stepped in to help save children in the US from polio. He suspected that peanut oil massaged into the skin would enter the body providing nutrients and reinvigorating wasted limbs. Indeed, he experienced some success with the method, and soon people lined with their children, hoping for “Carver’s cure.” He worked tirelessly for months and managed to help many children. (Since Carver’s time, it has been determined that it was most likely the massage, as opposed to the curative power of the peanut, that improved limb function for victims of polio.)

Carver’s Personal Life

Though Carver loved children, he never had any of his own. Once he attempted to foster a boy at Tuskegee, but the boy did not have the disposition for hard work and study, and he eventually left Carver’s side. Carver never married, and although both of the books I read mention one woman who caught his eye, little came of that relationship. In Holt’s version of events (which presumably matches Carver’s own), she did not understand his devotion to his work; in Elliot’s version, Carver would not ask her to.

Since Carver’s death, there has been speculation that he did not marry because he was gay. And perhaps that was the case. I often found myself, reading about certain subtle details of his life, wondering if he might be gay. He was recently (2007) included in An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture based partly on Holt’s account of his life. Specifically, Holt describes Carver’s late-life devoted friendship with his assistant, Austin W. Curtis, Jr.

Carver willed his portion of the profits from Holt’s book to Curtis, and (perhaps notably), Tuskegee fired Curtis upon Carver’s death. But Carver was a private man, and he lived during a time when public figures were allowed truly private lives. In fact, failing to subscribe to the notion that his intimate life (or possibly his lack thereof) is our business, I feel I’ve said more than I should have. But I wondered about it, and I thought you might be wondering too, so there it is. If you want to know more on the subject, I leave you to the library shelves.

Carver’s Legacy

Over time (and partly owing to his speech before Congress), Carver became a famous and important man (back then, the meaning of the words famous and important were much more closely aligned than they are today), and his efforts attracted the attention of many other famous and important people. He became close friends with Henry Ford, for example. In fact, their affection was so great that late in Carver’s life, when he became frail, Ford had an elevator installed in Carver’s building at Tuskegee. Further examples of Carver’s famous and important visitors include the Prince of Wales, the Crown Prince of Sweden, the Vice President of the United States (and, after Booker T. Washington’s funeral, the President as well).

Carver received many awards and other forms of recognition. A museum was built in his honor at Tuskegee; the NAACP gave him an award for outstanding achievement; he was awarded a Roosevelt medal for distinguished service in the field of science; the University of Rochester awarded him a Doctor of Science degree. This list goes on, but in deference to Carver’s own disposition (and if you’ve made it this far, in deference to your time), I want to keep the focus on his more down-to-earth contributions, which I hope you’ve tasted throughout this article.

Toward the end of 1942, Carver fell down a flight of stairs and never fully recovered, eventually taking to bed. On January 5,, 1943, his friend and Tuskegee’s cooking teacher brought him a tray of food from which Carver accepted only a few sips of milk and spoke his last, “I think I will rest now.” And so he did.

Carver’s epitaph reads: “He could have added fortune to fame, but caring for neither, he found happiness and honor in being helpful to the world.”

What an amazing man.

* * *

Cheri Colburn is a writer and editor who brings books into being through her midwifery business, The Finished Book. Her “likes” include hiking, the sound of her children’s voices, and long days digging in the dirt. Her “dislikes” include dieting, deadlines, and quitting bad habits.

![[ File # csp7146390, License # 1195875 ] Licensed through http://www.canstockphoto.com in accordance with the End User License Agreement (http://www.canstockphoto.com/legal.php) (c) Can Stock Photo Inc. / Morphart](https://i0.wp.com/www.usrepresented.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/sweet-potato-cropped-canstockphoto71463901-2.jpg)